Questions for Lois Guarino About her Art*

When did you become an artist?

That’s one of those tricky questions where almost any answer sounds pretentious. But the truth is, I can’t remember not being an artist. Since I was a child it was always my core identity. I’ve always felt the need to create things. I make art to discover.

What inspires your life?

The interconnectedness of all living things.

What inspires your work?

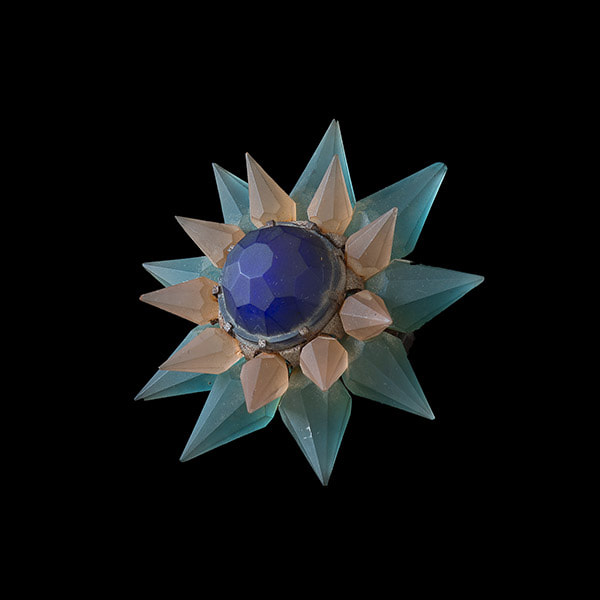

The big life questions. The magical. The ordinary. Objects. I’ve always had an unusual relationship to objects. I’m not a particularly materialistic person but possessing objects of all kinds is comforting to me because they are “stand-ins” for people or moments in time. The important objects resonate with memory and emotion. They all represent secret histories. Whether I’m making a photograph, a painting, a drawing, a short story or even a garment – it is an attempt to stop time or to make moments, feelings and people who I have lost, come back alive.

Can you explain more about your association with objects?

There have been psychological studies done that confirm that there is a human tendency to subconsciously associate an image of an object with the original object and to believe that this image shares an essential active relationship with the object itself. When something happens to (or in) the image, there is a non-rational belief that the object has changed as well. I have an extreme version of this belief system based on an entire life of relating to absent people through objects and the stories associated with them. It turns out to be a positive thing for me because I have used this to heal my own grief. I often think of my creative work as elaborate art therapy.

How much time do you commit to creating?

There is, not surprisingly, a direct correlation between how healthy and balanced I am with how much time I spend expressing myself. Since I have other roles in my life, including a demanding full-time job, it has been a complex dance to find enough time. I once viewed my creative life as more “opportunistic” than planned, with me filling in around the edges of my day if I found time. That was soul-starving and certainly not sustaining. Now I treat my need for expression as a very private and dedicated practice. I am in the studio at least once, or ideally, twice a day, no matter what. I write something daily, though not necessarily something to share with others.

In your dedicated practice, do you work even when you don't feel inspired?

I work when I’m connected to an idea or feeling that needs expression, which is just about all the time. I may, at times, feel tired or depleted physically, but I never feel uninspired. This may be because I have such a densely committed life and there is never enough time for all the creative projects I want to do.

You make photographs, paint, draw and write. With which medium do you most resonate?

The medium doesn’t really matter…except when it does. By that I mean I’m not attached to any particular form of expression so I pick the medium that best conveys what it is I want to say. There’s a big emotional component to it. An example would be my attachment to my Rolleiflex, which was my father’s camera. The pictures I made with it were more meaningful to me than the ones that I made using another camera. With photography having gone digital, that analog camera is now categorized as antique and classic; it has become one of the important items in my collection of useless objects. In recent years, painting has become very important to me. Not only do I have special brushes imbued with history and meaning, but I use fragments of memory captured via photography as my subject matter. Writing is a way to communicate in an even more direct way. When people relate to an image, they can put their own varied stories into the interpretation of the picture and this can be very removed from what I had intended. With words, I have more control over the story that is conveyed. I can also explore humor, which is generally not present in my visual art.

Is there a unifying thread?

Yes, for me, it’s all about making seen the unseen and capturing the things that one might not pay much attention to in everyday life.

Why do you paint pictures if you studied photography and spent many years of your life describing yourself as a photographer?

With painting, I get to explore something new and scary (I am untrained as a painter) and surrender to the discoveries, plus I get to really hone in, because of the medium, on the intimate details of my subject matter. Even though I can focus my camera on a person and capture great details, it is the camera capturing them; with painting, it’s me creating them.

Can you describe the process of creating through painting?

I do feel a little like a cannibal; I consume the subject with my paintbrush. After I’m done doing a portrait, I know the proportions, the bone structure, the exact shade of eye color, and the emotions behind the expression… in such an intimate way. It becomes about connection. When I start each painting (in the Complicated Grief series), I am driven by grief and the need to reconnect. And then after the paintings are finished, I feel a new connection and the absence of grief. The painting becomes an object. The object becomes a memory fetish, a substitute for the thing I lost. I like to be in the studio, surrounded by the finished canvases. It feels like a reunion. Old memories are revived. Moments that marked change are immobilized. People who have died are alive again.

I notice that you do this interesting thing in your paintings. It’s almost photographic, comparable to a shallow depth of field where something is in focus and other things are not.

In my paintings, I use detail to identify the most important emotional aspects. For example, in the painting “Making Art with my Father” the objects are the things with fine detail while the people, my father and me, are less detailed. My father’s shoe was given a lot of attention. This is because my only memory of my father is from age 2 when I ran to greet him and grabbed his pants leg. I do not have any visual impressions of him beyond his brown lace-up shoe.

How does photography relate to your paintings?

Every painting (in the Complicated Grief series) originates from a collection of existing photographs. I’m a collagist. I like to mess with time. For example, I used a photograph from 1948 (my father painting an abstract mural ten years before I was born) and a photograph from 1965 (me sprawled on the floor, drawing a fish four years after my father died) and I combined them, added to them, to create the real experience (unrecorded by any family snapshot) that I had as a small child when my sister and I worked beside our father in his basement studio. That feeling, that memory, is what is important to me.

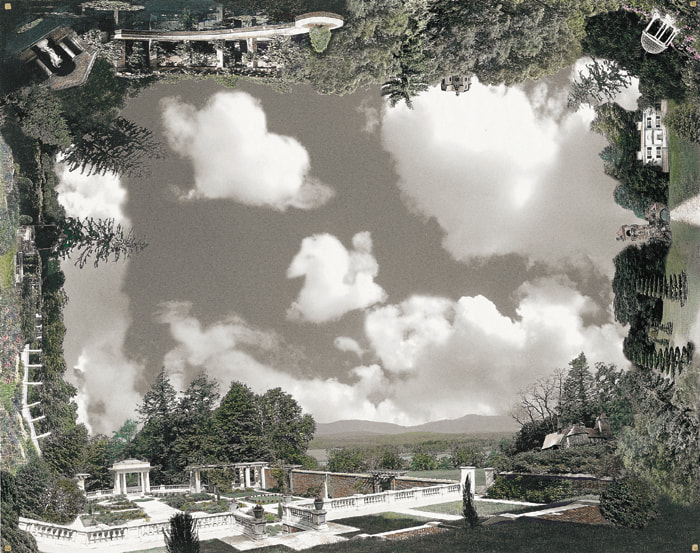

Other bodies of work are inspired by NASA photographs. Or by my own snapshots. For a while I photographed the sky every day. The Cloud paintings happened then. You see what you notice. While I was noticing the sky, I began to really see clouds, and love the forms. Painting clouds made me wonder about the unusual things that we take for granted simply because we get habituated as human beings on this planet. But clouds, if you study them, hanging overhead, are wonderfully odd and wonderfully ordinary.

Can you describe when you know you have completed a painting? How do you know when a project is finished?

I stumbled on a quote by Leonardo da Vinci recently that got me thinking. “Art is never finished. It is only abandoned.” I’d never viewed my work that way, though I understand the underlying message, which is that there is always more one can do. Always. But I work until it feels right. That’s more important than when it looks right. I paint to forge a connection to my subjects. I love it when a painting takes a long time because I get to “visit” with the person or the moment depicted. This “visiting” is enormously satisfying. A painting is finished when I have connected to the point where I can stand back, view the piece and feel in solid relationship to it.

Who do you paint for?

I paint for myself.

Who do you write for?

I write mostly for others. I use words to capture common experiences that hopefully other people can identify with.

Do you write about what you will be painting beforehand, or in the midst of the process?

Both. A creative project is a full-on relationship. It consumes my thoughts and spills into my other experiences. I keep an extensive journal and capture much of my process there.

What kind of space do you like to work in?

Since I get energy and inspiration from the objects I collect, my studio is full of them. Everything in life comes back to relationships and I have a relationship with each object…or, more accurately, with the person I associate with the object. So when I’m in the studio working, which is a solitary process, I’m never alone. I’ve got all those connections to people, all those stories behind the objects, all the beauty…and that energizes me.

When painting or photographing, do you listen to music?

I listen to music when I make anything (this includes preparing a meal!). I have bodies of work that, for me, are associated with a particular artist or song.

When writing what is your writing environment like?

I need quiet. I love to write in bed. There is something appealing about the cocoon of a quilt and the convenience of a laptop.

What’s your next big project?

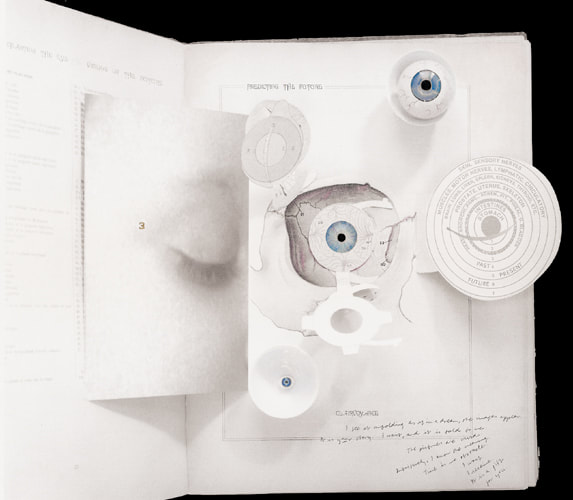

I have a number of projects queued up, just waiting for time to do them. Photography: a series of large-scale pop-ups, inspired by old medical and anatomy books; painting: a series representing my entire life timeline; writing: an illustrated story about compassionate service using the experiences of caring for my mother, Eleanor, in her final years, as well as what I learned from Henry, a rescue dog that I adopted at the same time; as well as finishing a collection of short stories called The Curriculum of Being Human.

* These questions were submitted by a number of people, including a writer, photographer, art historian, teacher and therapist.

When did you become an artist?

That’s one of those tricky questions where almost any answer sounds pretentious. But the truth is, I can’t remember not being an artist. Since I was a child it was always my core identity. I’ve always felt the need to create things. I make art to discover.

What inspires your life?

The interconnectedness of all living things.

What inspires your work?

The big life questions. The magical. The ordinary. Objects. I’ve always had an unusual relationship to objects. I’m not a particularly materialistic person but possessing objects of all kinds is comforting to me because they are “stand-ins” for people or moments in time. The important objects resonate with memory and emotion. They all represent secret histories. Whether I’m making a photograph, a painting, a drawing, a short story or even a garment – it is an attempt to stop time or to make moments, feelings and people who I have lost, come back alive.

Can you explain more about your association with objects?

There have been psychological studies done that confirm that there is a human tendency to subconsciously associate an image of an object with the original object and to believe that this image shares an essential active relationship with the object itself. When something happens to (or in) the image, there is a non-rational belief that the object has changed as well. I have an extreme version of this belief system based on an entire life of relating to absent people through objects and the stories associated with them. It turns out to be a positive thing for me because I have used this to heal my own grief. I often think of my creative work as elaborate art therapy.

How much time do you commit to creating?

There is, not surprisingly, a direct correlation between how healthy and balanced I am with how much time I spend expressing myself. Since I have other roles in my life, including a demanding full-time job, it has been a complex dance to find enough time. I once viewed my creative life as more “opportunistic” than planned, with me filling in around the edges of my day if I found time. That was soul-starving and certainly not sustaining. Now I treat my need for expression as a very private and dedicated practice. I am in the studio at least once, or ideally, twice a day, no matter what. I write something daily, though not necessarily something to share with others.

In your dedicated practice, do you work even when you don't feel inspired?

I work when I’m connected to an idea or feeling that needs expression, which is just about all the time. I may, at times, feel tired or depleted physically, but I never feel uninspired. This may be because I have such a densely committed life and there is never enough time for all the creative projects I want to do.

You make photographs, paint, draw and write. With which medium do you most resonate?

The medium doesn’t really matter…except when it does. By that I mean I’m not attached to any particular form of expression so I pick the medium that best conveys what it is I want to say. There’s a big emotional component to it. An example would be my attachment to my Rolleiflex, which was my father’s camera. The pictures I made with it were more meaningful to me than the ones that I made using another camera. With photography having gone digital, that analog camera is now categorized as antique and classic; it has become one of the important items in my collection of useless objects. In recent years, painting has become very important to me. Not only do I have special brushes imbued with history and meaning, but I use fragments of memory captured via photography as my subject matter. Writing is a way to communicate in an even more direct way. When people relate to an image, they can put their own varied stories into the interpretation of the picture and this can be very removed from what I had intended. With words, I have more control over the story that is conveyed. I can also explore humor, which is generally not present in my visual art.

Is there a unifying thread?

Yes, for me, it’s all about making seen the unseen and capturing the things that one might not pay much attention to in everyday life.

Why do you paint pictures if you studied photography and spent many years of your life describing yourself as a photographer?

With painting, I get to explore something new and scary (I am untrained as a painter) and surrender to the discoveries, plus I get to really hone in, because of the medium, on the intimate details of my subject matter. Even though I can focus my camera on a person and capture great details, it is the camera capturing them; with painting, it’s me creating them.

Can you describe the process of creating through painting?

I do feel a little like a cannibal; I consume the subject with my paintbrush. After I’m done doing a portrait, I know the proportions, the bone structure, the exact shade of eye color, and the emotions behind the expression… in such an intimate way. It becomes about connection. When I start each painting (in the Complicated Grief series), I am driven by grief and the need to reconnect. And then after the paintings are finished, I feel a new connection and the absence of grief. The painting becomes an object. The object becomes a memory fetish, a substitute for the thing I lost. I like to be in the studio, surrounded by the finished canvases. It feels like a reunion. Old memories are revived. Moments that marked change are immobilized. People who have died are alive again.

I notice that you do this interesting thing in your paintings. It’s almost photographic, comparable to a shallow depth of field where something is in focus and other things are not.

In my paintings, I use detail to identify the most important emotional aspects. For example, in the painting “Making Art with my Father” the objects are the things with fine detail while the people, my father and me, are less detailed. My father’s shoe was given a lot of attention. This is because my only memory of my father is from age 2 when I ran to greet him and grabbed his pants leg. I do not have any visual impressions of him beyond his brown lace-up shoe.

How does photography relate to your paintings?

Every painting (in the Complicated Grief series) originates from a collection of existing photographs. I’m a collagist. I like to mess with time. For example, I used a photograph from 1948 (my father painting an abstract mural ten years before I was born) and a photograph from 1965 (me sprawled on the floor, drawing a fish four years after my father died) and I combined them, added to them, to create the real experience (unrecorded by any family snapshot) that I had as a small child when my sister and I worked beside our father in his basement studio. That feeling, that memory, is what is important to me.

Other bodies of work are inspired by NASA photographs. Or by my own snapshots. For a while I photographed the sky every day. The Cloud paintings happened then. You see what you notice. While I was noticing the sky, I began to really see clouds, and love the forms. Painting clouds made me wonder about the unusual things that we take for granted simply because we get habituated as human beings on this planet. But clouds, if you study them, hanging overhead, are wonderfully odd and wonderfully ordinary.

Can you describe when you know you have completed a painting? How do you know when a project is finished?

I stumbled on a quote by Leonardo da Vinci recently that got me thinking. “Art is never finished. It is only abandoned.” I’d never viewed my work that way, though I understand the underlying message, which is that there is always more one can do. Always. But I work until it feels right. That’s more important than when it looks right. I paint to forge a connection to my subjects. I love it when a painting takes a long time because I get to “visit” with the person or the moment depicted. This “visiting” is enormously satisfying. A painting is finished when I have connected to the point where I can stand back, view the piece and feel in solid relationship to it.

Who do you paint for?

I paint for myself.

Who do you write for?

I write mostly for others. I use words to capture common experiences that hopefully other people can identify with.

Do you write about what you will be painting beforehand, or in the midst of the process?

Both. A creative project is a full-on relationship. It consumes my thoughts and spills into my other experiences. I keep an extensive journal and capture much of my process there.

What kind of space do you like to work in?

Since I get energy and inspiration from the objects I collect, my studio is full of them. Everything in life comes back to relationships and I have a relationship with each object…or, more accurately, with the person I associate with the object. So when I’m in the studio working, which is a solitary process, I’m never alone. I’ve got all those connections to people, all those stories behind the objects, all the beauty…and that energizes me.

When painting or photographing, do you listen to music?

I listen to music when I make anything (this includes preparing a meal!). I have bodies of work that, for me, are associated with a particular artist or song.

When writing what is your writing environment like?

I need quiet. I love to write in bed. There is something appealing about the cocoon of a quilt and the convenience of a laptop.

What’s your next big project?

I have a number of projects queued up, just waiting for time to do them. Photography: a series of large-scale pop-ups, inspired by old medical and anatomy books; painting: a series representing my entire life timeline; writing: an illustrated story about compassionate service using the experiences of caring for my mother, Eleanor, in her final years, as well as what I learned from Henry, a rescue dog that I adopted at the same time; as well as finishing a collection of short stories called The Curriculum of Being Human.

* These questions were submitted by a number of people, including a writer, photographer, art historian, teacher and therapist.

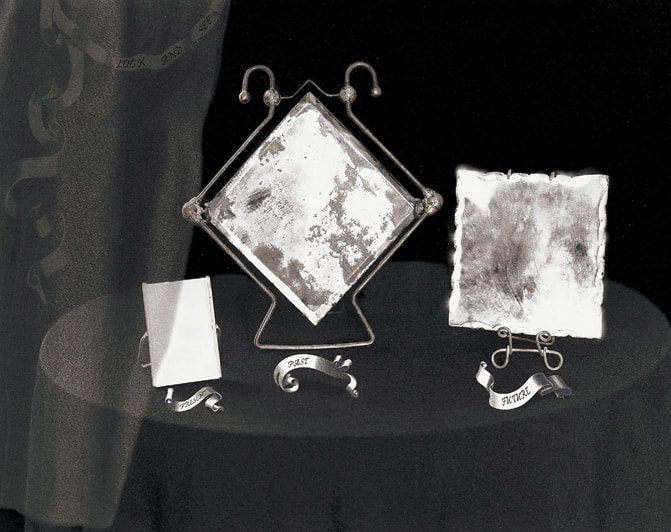

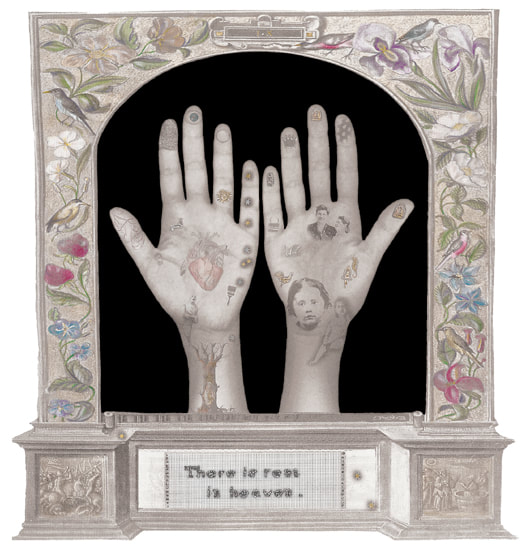

From the book of photographs entitled Wonders Miracles & Magic

A Conversation about the Work

Miriam Seidel writes about art for Art in America, as Corresponding Editor. This conversation with Lois Guarino took place by e-mail in May 2000.

MS: You added digital manipulation to an already wide array of techniques for altering your photographic images: the use of multiple negatives, cliché-verre, hand coloring and gilding. Did this change the “feel” of your working method?

LG: Yes, considerably. In the days when I constructed my pictures exclusively in the darkroom, I made one-of-a-kind images. They were labor-intensive, and often it was difficult to fully express the vision I had in my head because the technical control over the image was more primitive and limiting. Now, I merge computer technology with traditional photography and create any reality I imagine. The process of assembling a digital image is uniquely satisfying. I can work for days or weeks on one picture – much more like the creation of a painting than a photograph.

MS: You have mentioned the loss of your father as a formative experience. And some of your photographs

do have a sense of reaching across, attempting communication with the other side, almost seance-like. It makes me think how photographic images are in a way like ghosts, disembodied emanations of their subjects. Could you talk about this as an aspect of your work?

LG: My father was an artist. When I was growing up, he held a powerful place in the family, even though – or because – he had died. His presence in our house was apparent in all the objects he left behind. Each object represented aspects of his life and had a story connected to it. I was raised on these stories. I liked using his things, like his art supplies and papers, because it made me feel closer to him. One of the most precious of his objects was a Rolleiflex camera. What motivated me to make my first pictures was the desire to establish a relationship with my father – to see the world the way he might have seen it – using his camera. Of course I ended up learning a lot more about myself than about him.

Using the camera to record life the way I saw it was an amazing experience. I never wanted to record what was there. I wanted to record a world of my own making, the world of “otherness” where imagination and fantasy and faith in the mystical merged.

I have a serious interest in spirit photography. I’m drawn in by the idea of visually capturing the “other world.” I actually own a spirit photograph from the late Victorian era, and seeing this invisible realm concretely on paper is very comforting. I know it was for the Victorians who sought out photographers to reunite them with their beloved deceased. It helped with the grieving process. The question of whether these photographs were “real” ultimately doesn’t matter.

My family’s snapshots were equally comforting for me when I was growing up. Again, it was “another world,” a world where my father lived, where my relatives were youthful and vital. There was proof of life, because it was captured on paper. A potent childhood memory for me is of sitting in my paternal grandparents’ living room and experiencing my family’s version of a “spirit photograph.” My grandmother, a deeply spiritual Danish woman, had a full body photograph of my father enlarged to nearly life size. She hung it on the wall between two windows and placed a filmy white curtain over it. It was an incredible presence in the room.

MS: You have been recording your dreams for quite some time. It seems that the connection between your dream life and your photographs is both more unusually developed and more deliberate than that connection is for many artists.

LG: I began keeping a record of my dreams about thirteen years ago, and I’ve never missed a night. This regular contact with my interior life has been a necessary part of my well-being. It is my practice. I do it religiously. It grounds me, inspires me and forces me to use words, not just pictures, to describe things. This balance has been important.

My interest in dreams is closely linked to my interest in the subject matter of the Predicting the Future series of photographs. In my late twenties, I had a rather unusual dream that turned out to be precognitive – it predicted, by about twenty-four hours, an accident that happened to a friend who was traveling in France. I wrote down the narrative of my vivid dream in great detail, including the patterns on the clothing of the people involved. When my friend came home from his trip, we compared our accounts of the experience and were astounded by the complete overlap of facts. This dream woke me up, so to speak! I began to question a lot of things that I had dismissed or taken for granted before. I still have more questions than answers, but the photographic exploration keeps the interior dialogue going.

I have translated complete dreams directly into photographs, but most often dream elements become incorporated into my work. A snippet here, a portion of another dream there. When I first started the Dream Transformations series, I sent out a letter to a wide range of friends and family asking them to write down and send their dreams to me. I hadn’t fully realized what an intimate request this was. Only about twelve people sent me a dream – people guard their dream lives carefully, fearing too much might be revealed. I intended to “visualize” their writing, but I found it extremely difficult. It wasn’t personal enough for me. The only one who supplied me with a dream that I could actually translate was my six-year-old daughter. Her dreams are so closely connected to me and to my life experiences that it felt as if I’d dreamed it myself.

MS: The procession of horses and reindeer across the bottom of The Fever Vision, from the Origin of Carla series, has a strong flavor of the Paleolithic and shamanistic. In shamanic practice, dreams and visions are closely connected, in a sense are the same thing. Are dreams and photographic visions or images that closely tied for you? Do you identify with shamanism as a template for your artistic practice?

LG: The Fever Vision, an image of my sister and me, is a depiction of a hallucination I experienced during a childhood illness. I saw this magical parade of primitive animal shapes moving like a caravan across the ceiling of my mother’s bedroom and disappearing into the top of the closet. I remember being entertained by the electric colors of the animals and I remember totally accepting this “vision” as real. There is definitely a connection between the kind of acceptance that I felt then for this vision and the level of acceptance that used to be granted to the photographic image. At one time, “the photograph never lied.” Of course, now, with digital imagery, photography has lost that convincing factor. But I’m still a believer.

My artistic practice is guided by an intuitive process that is hard to put into words. It is more about personal archaeology than shamanism. I make pictures to expose questions for myself. It is about digging around and reconstructing the past and bringing the past into the present. Or, perhaps it is more connected to psychometry than anything else. The premise behind psychometry is that an object owned and used by a person takes on the energy of that person. The soul is imprinted on it – enough so that the story of the owner’s life can be read by holding the object.

My relationship to objects developed early, from the time that I was three or four years old, as I tried to piece together the story of my father’s short life through the possessions and creations he left behind. My mother saved everything. A lot of his artwork and materials were stored in the basement of our house. Basements are creepy places. I’d go down there to look at or borrow some of his things, but I’d always run – fast. His life imprint was so strong in that space. It was exhilarating, but it was also frightening. When I’d slam the basement door behind me, object in hand, it felt like I had gone on a dangerous adventure, a risky archaeological dig. One motivation in making pictures is to re-experience that intense feeling – a connection with a world where the realms of the material and the spiritual mingle.

MS: The Predicting the Future series is a compendium of different methods of divination and calls into play your love of objects. In much of your work, you seem to have a comfortable affinity with what feels like an older form: an eighteenth-century museum or a nineteenth-century cabinet of curiosities. Have you thought about this and how your working environment reflects such an interest?

LG: My first jobs out of art school were in museums. -There was one year when my office was off the Egyptian wing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and I found it thrilling to commute by the mummies and religious artifacts going to and from work. Although I no longer work day to day in a museum, my art studio and, to an extent, my home have become a small private “museum” of favorite objects.

I am drawn to objects with a lot of history, things that connect to memories, although a lot of the things I’m attracted to are not directly linked to my own conscious memories. If I went about collecting based only on my own memories, I’d have an array of mostly modern objects. I grew up surrounded by the simplicity of design from the fifties and sixties. We had Charles Eames chairs in the dining room and abstract expressionist artwork on the walls. But inexplicably, instead I am drawn to elaborate objects that are mostly pre-twentieth century, in particular things that refer to the medieval and the Victorian periods. They can be ordinary things, like a picture frame, sewing notions, a mirror or handmade clay marbles, or more unusual objects, like a gilded treasure chest, an icon, or enormous copper Pegasus wings.

Most of these objects end up in my artwork. I have large glass cabinets filled with them. They are the sources for pictures. I also have an “idea board” that I use as a place to bring my random thoughts and fancies into a cohesive whole. On it I put clippings from newspapers – usually those rare stories about a miraculous, unexplainable human event – as well as snapshots, playing cards, children’s drawings . . . anything inspiring.

MS: You play very interesting games of spatial compression and rearrangement. What do you feel

you are doing with these spatial distortions?

LG: I think my use of space is directly related to my lifelong interest in collage, and perhaps to the influence of all that abstract expressionist artwork that I was raised on. In art school I studied with Jan Groover, who was the first person to point out that I do something rather unphotographic within my photography. She noted that I tend to flatten the pictorial space so that shapes interlock, making for tight compositions. I guess this is one way to “control” the picture. And, after all, collage or assembled imagery is on some level about control.

Constructing a photograph – creating a realm where the rules are of my own making – is a powerful thing. The compressed space or slightly distorted perspective is consistent with the world of dreams, where ordinary guidelines do not apply. I find that world intriguing. I feel comfortable there.